Lung Cancer Causes – Genetics

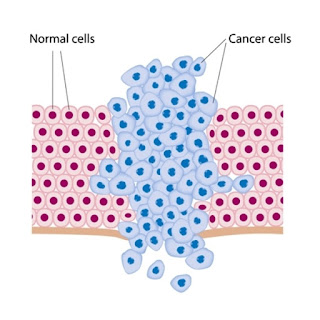

Genetic mutations that cause cancer

generally occur in two types of genes:

- Tumor-suppressor genes, which prevent cells from endlessly copying themselves

- Proto-oncogenes, which encourage cells to keep making copies of themselves [when a proto-oncogene changes (becomes mutated), it is then called an oncogene]

- Damage to either type of gene can cause a mutation that results in uncontrolled division of cells. This uncontrolled division forms tumors.

Cancer can be the result of a

genetic predisposition that is inherited from family members. It is possible to

be born with certain genetic mutations or a fault in a gene that makes one

statistically more likely to develop cancer later in life. Genetic

predispositions are thought to either directly cause lung cancer or greatly

increase one's chances of developing lung cancer from exposure to certain

environmental factors.

Lung cancer is the most common

cause of cancer death worldwide, with over one million cases annually. The

five-year relative survival rate for lung cancer is only 10-15%. In

approximately 90% of the cases, cigarette smoking is the main etiologic factor.

We often associate lung cancer with

tobacco, but 25-year-old Matthew Hiznay is a lung cancer patient who never

smoked a cigarette. He is battling a rare form of genetic lung cancer for the

second time in less than two years.

Screening tumor samples for

cancer-causing genetic mutations can help physicians tailor treatment to

specifically target those mutations in patients with advanced lung cancer.

Other risk factors include radon

exposure, or exposure to nickel-, chrome-, cadmium-, arsenic- and asbestos

compounds. Lung cancer sometimes aggregates in families, suggesting that

genetic predisposition may also play a role in the development of lung cancer.

It is unlikely that a single

specific abnormality causes all lung cancer. It probably takes a variety of

mutations to start the devastating chain of events leading to cancer. The

following mutations are among those under investigation:

- EGFR mutations: EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor gene) is a family of genes that can mutate and promote tumor growth. This gene mutation is often implicated in non-smokers. HER2 is a related gene under study that plays a role in regulating cell growth.

- BPDE-caused mutations: The chemical BPDE, a byproduct of tobacco smoke, is involved with a number of genetic mutations, including those to an oncogene called K-ras and to three tumor-suppressor genes known as p53, PPP2R1B, and p16. (Tumors that contain the p53 mutation may also be more resistant to chemotherapy.)

- Rb mutations: Another important contributor to lung cancer is a genetically defective protein called retinoblastoma (Rb), which is associated with very aggressive tumors. Low levels of the normal Rb gene may sometimes predict aggressive cancer, especially in patients with small cell lung cancer.

- Abnormalities in the FHIT gene: Such abnormalities may cause the cells lining the lung to become more vulnerable to the effects of tobacco smoke and other cancer-causing substances.

- Alpha1-antitrypsin mutations: People who carry a common variation in the gene for alpha1-antitrypsin -- a substance that normally protects the walls of the alveoli in the lungs -- are 70% more likely to develop lung cancer than those without the mutation, regardless of whether they smoke.

- Many other gene mutations have been implicated including BRCA1,RAP80, RRM1, ERCC1, and TS. Scientists continue to explore the complex relationship between various genes that play a role in cell production and what environmental factors give rise to cancer.

- Medical centers are beginning to test tumors for specific gene mutations affecting tumor growth. The hope is that an accurate "genetic fingerprint" can help doctors prescribe the most effective and appropriate treatment options.

When Hiznay was about to begin his

second year of medical school at the University of Toledo College of Medicine,

a persistent dry cough sent him to his family doctor, who made a preliminary

diagnosis of a lung disease — sarcoidosis — and referred him to Cleveland

Clinic.

When Hiznay was about to begin his

second year of medical school at the University of Toledo College of Medicine,

a persistent dry cough sent him to his family doctor, who made a preliminary

diagnosis of a lung disease — sarcoidosis — and referred him to Cleveland

Clinic.

A new study detected one of ten

such mutations in 54 percent of the 516 lung cancer patients tested at

diagnosis. The results enabled doctors to select the most appropriate drug

designed to block the identified mutation and choose other treatment options

for those patients whose tumors did not have a mutation.

No comments:

Post a Comment